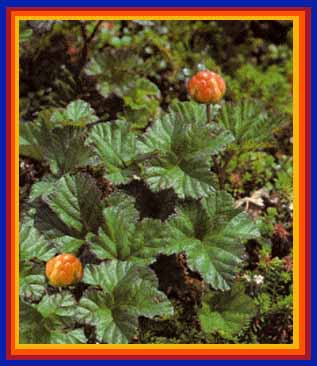

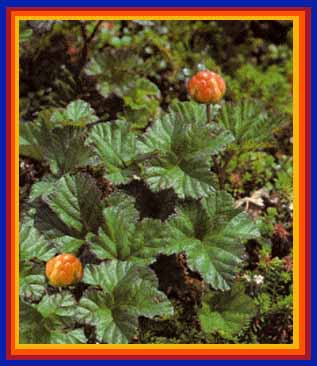

Rubus chamaemorus is the official botanical name for "Cloudberry," known also to the locals as "Baked-Apple Berry." It is also one of several species called "salmonberry." Marilyn Walker, in her book Harvesting the Northern Wild (3), describes these as a low or creeping raspberry that has no prickles on its stems or leaves. I don't really feel comfortable defining this plant as a raspberry. As a Rubus species, Cloudberries are certainly close relatives of raspberries, but they show too many differences for me to want to lump them in with their better-known relatives.

Brandson and Chartier(1), quote the observations of Andrew Graham, an early explorer. "It [cloudberry plants] grows in a dry mossy soil, is of the form of a strawberry, but near thrice as large and of a deep yellow. It seems glutinous when eaten raw; but is very agreeable when made into tarts, and has much resemblance in taste to apples. ... "The shrub which produces them is not thicker than coarse sewing twine. It runs for several yards on the ground before it penetrates through the moss and just emerges at its end, to produce a white flower similar to the daisy, but much inferior in size; to this succeeds the fruit or berry. There is only one berry to a stalk." (1b)

According to Johnson, cloudberry comes from a creeping rootstalk. "The flower is white, solitary and borne at the tip of the stem and is either male or female, with the opposite flower parts present but in a reduced and non-functional form." Cloudberry flowers in June and July, fruits in August.

Marilyn Walker explains that many of the fruits of this plant, called "bethago-tominich" by certain Indian groups, are composed of only 3-4 lobes, and that it is soft and juicy when ripe, difficult to carry and, in mild disagreement with Andrew Graham, considers it delicious right off the plant. Cloudberries were considered a great antiscorbutic by early explorers such as Samuel Hearne.(1c)

Nowadays, cloudberries are locally gathered mostly to be processed into small jars of jelly to sell as souvenirs to tourists. I bought one myself while shopping in Churchill at The Eskimo Museum gift shop. The jelly is a beautiful clear yellow and did indeed taste something like apples.

As is the case with all of these far northern fruits, cloudberries are circumpolar in distribution. The American Indian Ethnobotany Data Base, published over the World Wide Web,(4) maintains information on research sources that describe traditional uses of plants by various aboriginal peoples on the North American continent: According to A.E. Porsild (1953, Edible Plants of the Arctic.) Eskimos beat chewed caribou tallow with seal oil until it was fluffy then mixed in cloudberries to create a confection called "Eskimo Ice Cream." The Upper Tanana of the Pacific Northwest fried the berries in grease, with sugar or dried fish eggs. (Priscilla Russe Kari, 1985 Upper "Tanana Ethnobotany." Anchorage, Alaska Historical Commission (12).) According to Michael R Wilson, the Inuktitut ate the berries fresh, frozen or mixed with oil or fat ("Notes on Ethnobotany in Inuktitut." The Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 8:180-196 (183) 1978.)

This same database also revealed how aboriginal peoples utilized cloudberry plants for medicinal purposes. A.L. Leighton, ("Wild Plant Use by the Woods Cree (Nihithawak) of East-Central Saksatchewan," published 1985 by National Museums of Canada, Mercury Series (56)) describes how the Woods Cree would brew a decoction of the root and lower stem to be used by barren women and also to ease hard labor. The Micmac used its roots for consumption, cough and fever. (R.F. Chandler, L. Freeman and S.N. Hooper 1979 Herbal Remedies of the Maritime Indians. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1:49-68)(61).)

Many modern herbals recommend raspberry leaf tea for women suffering from bad menstrual cramps and female complaints in general, and I've personally known people who swear by it. According to Katie Letcher Lyle, author of "The Wild Berry Book, Romance Recipes and Remedies," "a substance in the leaves of red raspberries, variously called framamine, fragrine or fragerine, isolated in the 1940s, strengthens, relaxes and tones the uterus, thus exonerating the old wives' advice that raspberry tea should be taken throughout pregnancy, labor, and postparturition. The leaves, according to modern analysis, are also high in magnesium, which is still in use to prevent miscarriage." Maybe the same useful chemical occurs in all the Rubus species; if so, the Crees were intuitively correct in using Cloudberry plants to help female problems.

One sunny day while bundled inside my bug jacket and reeking of 100% Deet, I found a number of cloudberry plants growing on a slope and along a ridge by the side of a lake about a quarter mile downhill from the Churchill Northern Studies Centre in an area somewhat drier than the ankle-deep mud nearby. Each plant reached barely to the top of my foot. The leaves I saw were bright green, prominently veined and lobed but not actually divided into leaflets as is its close relative the stemless raspberry. The general appearance, however, is definitely, strongly Rubus. You would know, just by looking at it, that it had to be related to raspberries and blackberries. Unwilling to disturb native fruit plants, I didn't do any digging to take a closer look at the structure.

On that July afternoon when I came upon them, a few of the cloudberry plants were in early fruit. The others, although beyond the flowering stage, had not yet developed visible fruits or else were plants that had produced male, therefore non-fruitbearing, flowers. I estimated the immature cloudberries to be about half an inch around and bright red. As they ripen, they would fade to salmon, finally becoming yellow when ripe.

I wish I had taken, right then, photographs of those few plants in early fruit , but the area's ferocious bugs had been plaguing me despite my protective armor. In their urgency to feed, mosquitoes and huge blackflies almost the size of olives had been throwing themselves at my face and bare hands. They were even crawling inside my clothes through the neckline. Swearing at them didn't help, although if swear words could have killed them, the afternoon would have become bug-free. As I felt stingers injecting themselves into my veins and arteries, and horrid mandibles tearing chunks out of my legs, face, neck and scalp, I wanted only to get indoors. I promised myself that I'd come back on a cooler day or when the wind was blowing. I comforted myself in the knowledge that if it weren't for these powerfully intense insects, land developers would probably have trashed such a beautiful place with their condos, beachfront hotels and strip malls.

When I finally returned, on my final day at the Centre, I found not a

single cloudberry plant in fruit. I thought I had returned to the same place,

but probably had not. The landscape, although beautiful, is somewhat featureless.

I had probably strayed a few yards to the left or right of my original position.

Oh well, next time, later in the summer.

Sources:

"Wildflowers of Churchill and the Hudson Bay Region," Karen

L. Johnson. (published by Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, in 1987)

Harvesting the Northern Wild, Marilyn Walker, The Northern Publishers,

Box 1350 Yellowknife, NWT X1A 2N9, 1984;

The Flora of Churchill, Manitoba 7th edition, 1991 by Peter A. Scott, Dept. Zoology, U Toronto 25 harbord Street, Toronto, Ontario CA M5S 1A1

Go To Crowberries

Return to Fall Fruits

Return toBotanizing in the Region Created 1/31/97